NB: This is not meant to be part of the Alchemists and Blood Merchants series. I felt compelled to push out this one because of an extended post I came across on X. I found it so apt and so rare a take on the underdevelopment question of Nigeria and the rest of the lower world. Also, it chimes effortlessly well with some of what I have written in the recent past, especially my contribution to the global IQ debate at Woods From Eden Substack. Consider this a detour I couldn’t resist.

Two days after the announcement of Gen. Buhari’s death, I encountered two interlinked tweets by a Mr. Possible on X that resonated deeply with my own sentiments. I was completely absorbed into the spirit and letter of Mr. Possible’s tweets that I was soon nodding in agreement with the very uncommon, but clear-headed arguments put forward in them. The initial relatively shorter tweet was a response to a brief, seemingly innocuous tweet by another user, while the second tweet was a bulkier elaboration on the first.

To provide the context as well as the impetus behind the two tweets in question, the immediate former president of Nigeria, Gen. Muhammadu Buhari, was announced dead on the 13th of July, much to the shock of everyone. While everyone had become used to regarding him as medically and physically frail, very few people knew he was terminally ill. However, reactions to his death have been strongly divided as well as divisive. On the one hand are those who believe he was a saint, a hero, a savior, a revolutionary, a paragon of all earthly virtues, and so on. On the other hand are those who see him as a wolf in sheep’s clothing, the devil’s incarnate in disguise, a clone from Sudan, a useful idiot, a tribalistic sadist, a brutal tyrant, and so on. And, of course, there are the in-betweeners, the “nobody is perfect” moral relativist crowd. The battle between these three groups on social media, especially X, has been brutal. But this is not an obit or audit of Buhari’s life and legacies. That’ll be adequately taken care of by better-qualified agents of historical documentation.

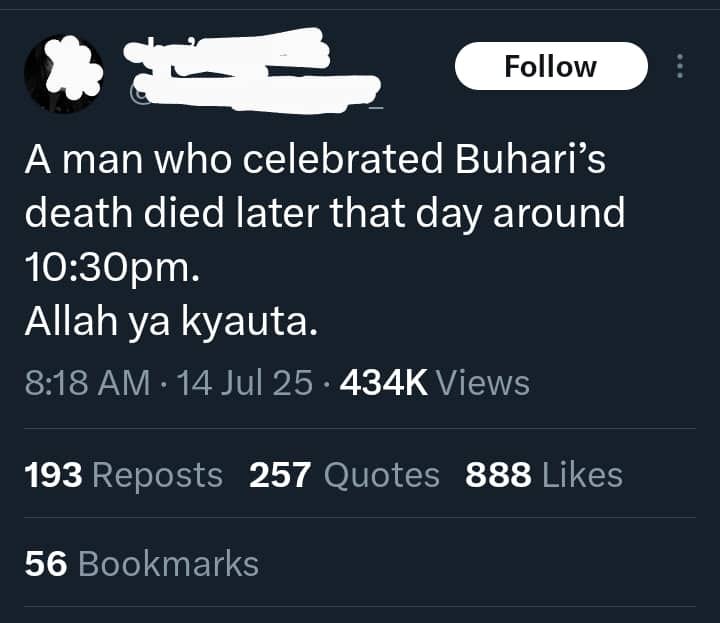

On X, another user, whose name suggests a northern origin (the same region, and perhaps the same ethnic group, as Buhari), had tweeted the claim in the screenshot below the morning after Buhari’s death was made public:

This lady’s tweet clearly implied that responding to the ex-president’s death with anything other than grief was dangerous—and that anyone who dared express a contrary emotion risked swift, life-ending retribution from Allah. Of course, the overwhelming majority of the responses that followed mocked the tweet. Yet, I’m certain that the majority of the people who pushed back against her belief did so not because they disagree with its fundamental premise but because it was applied to a figure much hated. Let the same belief be expressed in the service of a figure beloved by their own constituency, and you see the hostility reversed or reshuffled, depending on the situation. This was no doubt a viral tweet considering the size of the account that tweeted it.

In any case, our mysterious Mr. Possible was one of the good citizens of X who took our lady’s modest tweet very seriously. And he was right to do so! What follows is a direct reproduction of his reactive tweets.

“I’ve been saying it for a while now that our biggest problem is not poverty; we are not the way we are because we’re poor. We are poor because of the way we are. When you mix unprogressive cultural practices and norms (developed by fairly stupid people) with bad leadership (constituted mostly by stupid people), you get a poor society. Poor in mindset, poor in morals, poor in integrity, poor financially.

We have a disproportionate amount of stupid people. And stupid people are more likely to be corrupt, greedy and incompetent because they have dangerously closed minds, they are easy to indoctrinate with dogma and ideologies and the worst of all, they are genuinely incapable of thinking about the meta consequences of their actions because they do not see the connection between actions and long-term effects. It’s a pity.

Vacant superstition is extremely low intelligence, and if you have a huge population of low-functioning youths, you neither have a great society nor can you bet on the future. What’s the point of having the numbers if the majority are mediocre minds? They become a problem, not an advantage. Especially if the majority of electoral decisions rest in the hands of those most likely to be uneducated and senselessly indoctrinated”

End of first tweet.

“Here is the Nigerian dilemma, in my view. This may be long and I’m typing on the fly, so take it as it is. Whichever way you look at it, it begins with leadership. Disciplined, visionary leadership. But not leadership alone. The transformation of a society’s collective intelligence is ultimately a project of social engineering. Formal education is only a fragment of the architecture.

The deeper truth that all civilized societies have clocked is actually metaphysically sound: your environment is intelligent. If it weren’t, you wouldn’t be. Intelligence is not merely an attribute of individuals, it is a property of systems. To improve the collective, you must make the system more intelligent. That means working with the best of the best minds to design institutions that reward foresight, enforce laws that reflect global best practices, regulate stupid and unproductive cultural norms, and building a society where education is not just encouraged but compulsory, competitive, and constant.

But here lies the central paradox: only an ensemble of highly intelligent, exposed, and altruistic people can build such a system. At least if you insist on practicing a democracy. Unfortunately, democracy requires them to be elected by the very population whose intelligence is in question. That’s the Nigerian (and I dare say) African tragedy. The people most in need of structural reform are least equipped to recognize or support the kinds of leaders who can deliver it. And there are just too many of them, ironically concentrated in the part of the country with the most important electoral numbers.

The issue isn’t that stupid people are inherently malicious. In fact, maliciousness cuts across all cognitive levels. The problem is that those with lower cognitive range struggle to perceive long-term, collective, win-win strategies. They just can’t see the need for it. Conduct elections 1,000 times, they would feel more moved to take that 5,000 naira today and suffer tomorrow. The impulse is so strong, which is why you can’t allow a society, a business or an institution be run by idiots. Even when they don’t mean it, they will ruin it, because they, too, need to be managed. So they revert to short-term, self-serving impulses that ultimately erode the very fabric of society.

Even if, and this is a big if, we manage to install such rare, enlightened leadership across all levels of governance (we haven’t even succeeded at the presidential level), we still face the economic and infrastructural debris left behind by decades of short-sighted, extractive rule. To even think about social engineering at scale, you have to fuse improvements in monetary policies to reflect in fiscal policies and ultimately in the cost of living. You have to have the infrastructure necessary to enable you carry out your plans. Only after clearing that rubble can we begin to engineer the kind of society we dream of: one governed by rule of law, high educational standards, and ruthless enforcement of public interest. The painful truth is that such a future is hard to imagine in Nigeria today. To make matters worse, the best minds are leaving. And make no mistakes, they’re not as many as you think. Even if you think Nigeria has 10 million geniuses (which it doesn’t), in a pool of 200 million people, that is still insignificant. Yet, the few we have, are massively emigrating. And can we blame them? You only get one life. There’s little incentive to pour your best years into a broken system when mediocrity is rewarded, and excellence is exiled.”

End of second tweet.

This is one of those rare opinions that, once expressed, leaves me with nothing to add or subtract. In one of my previous articles, I used the metaphor - “impressionable wild child” - to describe my impression of Nigerians as a people. But this is, in fact, a universal sensibility, continuously felt by those few who are both morally and intellectually ascendant toward those who occupy the lowest strata of these two broadly human attributes. Thus, Mr. Possible’s tweets faintly re-echo a point I made in the comment section of an article by Tove K, titled 'We Need to Think About Africa.

“The overwhelmingly predominant attitude among the educated elite in Africa is that Africa's problem has nothing to do with cognitive disadvantage and more to do with Western oppression or bad leadership or colonialism or... whatever other external agent they can think of. One of the consequences of low IQ is the inability to organize at scale and mobilize collective actions while setting a far reaching national goals that transcend tribal sentiments.”

In another essay of mine, I argued that the problem with the black race is less about their “cognitive capacities” and more about their “cognitive propensity”. The two aren’t even remotely the same in terms of how they manifest in the real world, and it is the latter cognitive quality that is more susceptible as well as more resistant to the influences of nurture and culture. Cognitive propensities, as I’m inclined to define them, are biologically engineered instincts that guide how core cognitive capacities are applied or invested. For example, the Yoruba used their impressive cognitive endowment in numeracy and language to build one of the most ingenious and intricate religious and cultural artefacts — the Ifa Corpus. Here is a cognitive propensity towards that which is supernatural rather than the technological, the narrative rather than the illustrative, the symbolic rather than the substantive, the mythic rather than the factual. One could argue that this was a very ancient achievement, and I’d respond that it’s a pity then that there has been no pre-modern or modern cultural invention to rival this piece of artefact.

Another very vital cognitive propensity captured in Mr. Possible's tweets is the preference for “designing systems”. Not just systems, but nearly self-sustaining and durable ones — ones that do not require the constant intervention of the 'big man,' 'the chief,' 'the elders,' or any man of power. Every sound mind is capable of design, however crude, yet only a rare few are innately disposed to perceive the world as scattered pieces of a vast jigsaw puzzle, awaiting assembly into a coherent whole. When enough of such minds exist within a particular culture, the culture will naturally gravitate towards deliberate environmental and social design, towards building systems, towards systematization as opposed to constant improvisation.