Alchemists And Blood Merchants - Part 1

Money rituals and the commodification of body parts in Nigeria.

An Abundance of Stories

News about kidnapping by suspected money ritualists is a staple of Nigerian media fest. Stories abound of and by persons who were fortunate enough to live to tell of their near-death ordeal in the hands of ritual killers. If you typed “escape from ritual killers” on Google1, you'd see endless stories of Nigerians who came close to becoming forgotten victims of ritualistic money hunters. And these were just the very few who survived to tell their tales. For every victim who survived, there are maybe at least 50 or more who didn't. These stories cut across state, LGA, and demographic lines.

Here's a 2018 story of a 17-year-old secondary school student who was kidnapped by suspected money ritualists in Bauchi state and ended up in Kano. And here's another of a 50-year-old father of four in Lagos on his way to the airport to catch his return flight to London. And then there was the case of two 13-year-olds who entered a one-chance2 vehicle on their way back to boarding school in Benue state. The stories are endless and often gruesome in their details.

A Disturbing Phenomenon

There is no doubt that a disturbing sociocultural phenomenon almost unique to Black Africa, but particularly more prevalent in Nigeria, has been ravaging the country for at least 3 decades now: the pursuit and the use of specific human body parts (dead or alive) to allegedly synthesize money (not unlike how ancient alchemists pursued gold through dubious chemistry), attract wealthy/gullible patrons to their fraudulent businesses, procure political or spiritual power, or secure supernatural protection through fetish rituals of all sort. It's now a sort of national epidemic in Nigeria that hardly a week goes by without an array of news about another decapitated or harvested body being used for money ritual and sundry material benefits. If you’re a Nigerian based in Nigeria, the chance is very high that you know or have heard of someone who was a victim or a near-victim of ever-prowling money ritualists. But don't just take my word for it, here's an excerpt from a piece in one of Nigerian’s most recognized Newspapers, The Nation:

“Ritual killing is a common phenomenon in Nigerian daily life. It has become a regular event when hundreds of Nigerians lost their lives to ritual killers. The ritual killers go about in search of human parts – heads, breasts, tongues, and sex organs – as demanded by witch doctors, juju priests, traditional medicine men or women and/or occultists who require such for their dubious sacrifices or for the preparation of assorted magical portions.”

This may sound incredible, but kidnapping has become a notoriously multi-purposed criminal enterprise in Nigeria. This particular fact has two further implications. First, it is no longer a straightforward exercise to immediately pin down the primary motive (of which there may be many) for a kidnapping incidence. It could be as simple and direct as a play for ransom (perhaps the dominant motive within a narrow historical period, around late 2000’s to early 2020’s). Or it could be for human and organ trafficking - perhaps the least common kidnapping motive, but likely the most organized kidnapping enterprise. Or it could be for fetish motives with the objective of making some random dude rich, powerful, or famous (patrons are almost always males and culprits are often very young males). Second, the evolved multi-sectoral nature of kidnapping also means that it has over the years become an operation of well-delineated areas of sub-specialization within the whole criminal industry.

To further break this down, focusing narrowly on ritual-motivated kidnappings; there is the supply end and there's the demand side. At the supply end of this ritual economy are the herbalists, native doctors, Islamic and Christian spiritualists of certain persuasions. Still on the supply side you’ll find the actual kidnappers who prowl the road day and night in search of suitable victims (sometimes with specified characteristics); the sponsors who employ kidnappers, provide the holding dens for kidnapped victims who are then sold to those seeking money rituals or harvested body parts for medical purposes. There are many other minor players on the supply side of the ritual economy who are not directly involved in the transactional chain but help smoothen its operations. These would include your regular rogue police officer, a randomly conscripted commercial driver, a close associate or romantic partner of potential victims, etc. I call these last group in the supply chain secondary accomplices in the ritual economy.

On the demand side, you'll mostly find your typical underclass citizens as well as wealthy patrons desperate either for more material wealth (or the need to render it proof against misfortune or “the evil eye” or “the village people”3), political power, or spiritual fortification. Like kidnapping for ransom or for organ and human trafficking, kidnapping for ritualistic ends has evolved from its disparate and scattered beginnings into a well-coordinated enterprise. This news article pretty much captures most of the cast of characters (and more) included in my supply-demand analysis of this criminal enterprise.

A Brief Cross-cultural Glance

Does this kind of metaphysical crime occur in any other parts of the modern world outside sub-Saharan Africa? It’s difficult to answer with any degree of certainty. But my informed guess would be that it is very rare outside Black Africa. When I typed into Google search the phrase “global prevalence of money ritual”, all the relevant and applicable results in the first 8-10 pages were more or less focused on Nigeria. The only two results that centered on Kenya and Cameroon respectively had nothing to do with killing human beings specifically for money-making ends. And no single result is from anywhere outside sub-Saharan Africa. However, to the extent that this crime, broadly conceived, is observable in other parts of the world, it can be differentiated according to three yardsticks:

In other parts of the world, this particular kind of homicidal crime is often associated with extreme mental illness, organ replacement black markets, and pure ‘ol malice. In Africa, however, it is mostly perpetuated by very sane and culturally normal everyday people mostly for material and spiritual gains.

In other parts of the world, such crime is more often than not an end in itself. In Africa, it is often a means to an end, lending it a teleological power.

This higher end is often generally endorsed amongst most if not all Nigerians, either implicitly or explicitly (more on this point later), making it difficult to achieve implicit social consensus on the moral claim that: the end doesn't justify such a means.

Hence, there is often a deep and broad belief at the cultural level, at least in the potency if not the morality of money rituals that rely on human parts. It traces back to even older traditions such as those of appeasing the gods through human sacrifices. But the much older and culturally grounded tradition of sacrificing humans for religious purposes is still quite distinct from its uniquely modern counterpart. Aside the distinction in the ends being sought by slaughtering a living human being, human sacrifice is also further distinguished by the fact that it was more or less a universal phenomenon. These distinctions were well captured by a nameless “Senior Research Fellow from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka”, for the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Board Research Directorate:

Ritual killings are the act of killing human beings extra-judicially for the purpose of attaining temporal goals in life such as raw money-making, [or achieving] extra growth in business, banks, churches, political power as well as personal spiritual strength. On the other hand, human sacrifice is the offering of human beings to transcendental forces, such as deities for the purpose of either atonement for sins or seeking protection or related favour. In other words, while the latter is rooted in African tradition and legally practised within the time and space of pre-colonial African society, the former appears to be a contemporary phenomenon rooted in the modern quest for inordinate wealth and influence.

To further highlight these cross-cultural differences when it comes to commonly unearthed motives for the criminal use of human bodily exudates, let's examine one of the mildest examples: that of adding bodily byproducts (urine or bathwater in this case) to consumables, a less gruesome form of the ritualistic practice being discussed. I found instances of such cases reported across four different countries: the US, India, Cameroon, and Nigeria. In the US case, the primary motive of the young lady in question appeared to have been a mixture of some personality disturbance and desperation for online fame. The India case involved a woman employed as a housemaid. The motive wasn't stated but the act was probably born of malicious and vengeful feelings for some perceived injustice and/or grievance. The remaining two cases - Cameroon and Nigeria - were also women, but their motives, unlike the first two, were distinctly metaphysical and targeted at monetary ends. Of course, these are only known cases, there are many more that never make it into the news but well-known among citizens of these two African countries.

An Epidemic of Emergency Proportion

The menace of ritual killings in Nigeria was so dire at some point that members of the house of reps, in 2022, called for the then-president to declare a state of emergency. As an aside, let me state that in Nigeria, we are very good at declaring states of emergency for every problem under the sun, as if the mere declaration is an act of immense courage. Just to highlight a few of our stellar achievement in this domain of governance, we have valiantly declared multiple emergencies against illiteracy, flooding, electricity, and of course the king of all emergencies, insecurity. Our ruling class declare emergency for fun the same way they hand out stomach infrastructure4 hunger palliatives for fun. Surprisingly, these bold emergency declarations have yet to yield any of the solutions promised. It's often the case that the swashbuckling declarants are also, more often than not, active actors and perpetuators of the very problem they are confronting with the toothless weapon of emergency declaration. In Nigeria, the act of declaring a state of emergency has never really been about seriously tackling a problem, but more about creating an impression of doing so. Aside from your average street rascals, grassroot powerbrokers, election tribunal lawyers and magistrates, another group that is always excited with each election year cycle are the people operating within the money ritual economy. This is because politicians are often some of their biggest patrons.

Nothing New Under This Tropical Sun

Money-motivated ritual killings have been a menace in the country for more than 2 decades, but it appeared to have reached an unprecedented magnitude at the beginning of this current decade. It is impossible to pull out specific statistics to support this claim because there's none. Only media stories and of course streams of anecdotes of fatal and near-fatal encounters with ritualists (my own sister was a near-victim). However, to give a statistical inkling of how bad this phenomenon is, WENAP, a West Africa-based civil organization in collaboration with another NGO, Nigeria Watch, has been tracking violent incidents across West Africa since 2008. In their only report I could access, they reported statistics for "ritual-related deaths" specifically for the period between Jan 2021 and Jan 2022 (the same time period Reps called for a state of emergency). According to their metrics, there were 185 ritual-related deaths in this one-year period. Mind you, this particular statistical report relied mostly on news report by traditional prints media, and occasional reports from the Police Force. I came across another piece in the Nigeria Daily Trust in which the writer cited an NBS (National Bureau of Statistics) 6-month statistic of 150 ritual-related killings in the last half of 2024.

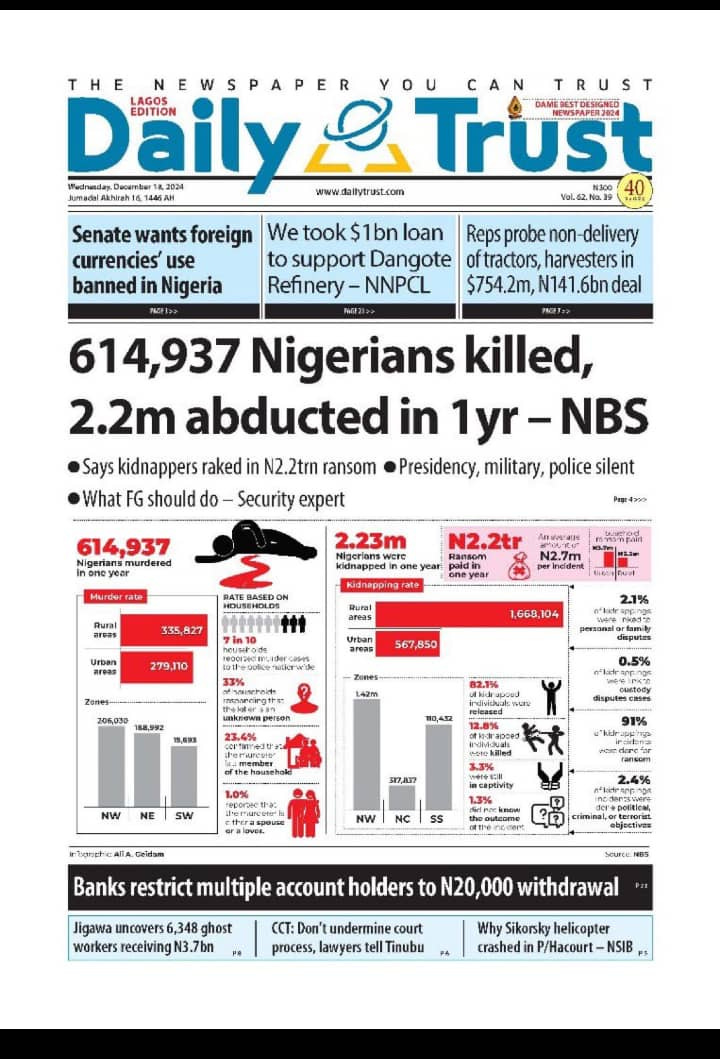

Any Nigerian would easily agree with me that the real number is likely to be 20x or more of what these official statistics captured. For instance, if we go back to the earlier image on the front page of Daily Trust showing one-year data about abductions and killings in Nigeria, it reported that 13.1% of total abductions (2.23 million) resulted in killing. In raw numbers, this translates to 292,130 deaths from kidnapping incidences. The question is, what percentage of these deaths were related to money rituals? My bet is, whatever it is, it is definitely not 0.06% - using the above 185 figure reported by WENAP and Nigeria Watch. Just like in cases of suicide and rape, available statistics always undercount the incidence rates, and this is even more so in a country with quality data-gathering problem (I’m, however, willing to say that the NBS has been doing an impressive job so far). To buttress with reportive evidence, take this news piece for example in which two arrested ritualists revealed that they alone have been responsible for killing at least 70 girls for money ritual purposes in the course of their relatively short career. Or this one, exposing one of the many dens spread across the country that are used as holding cells for captured human merchandise. Or take this even more chilling confession of one perpetrator allegedly on a live radio program. I think it's worth quoting a paragraph from the ensuing news report:

“My idol takes about 73 to 76 women for over seven years. These women are always gotten from the club or other popular places. When I eat people, it is purposely to renew the voodoo in my body. Sometimes, when I’m shot, it won’t penetrate, even when I’m hacked, the machete breaks. The sweetest human parts are tongue, palm, and foot.”

Now, imagine what a syndicate would achieve - and as already established earlier, there are ritual killing syndicates spread all over the country, involving even the most powerful and respected members of society. Here's another revelation from the same man in the above quote:

“I also work for bank managers, politicians, and some other rich men. I’m very popular among them. When I first worked with a bank manager, it was one wealthy man that we killed and the info was supplied in the bank.

“The only person who was left to sign refused to sign, we visited him, made him sign, and killed him aftermath. I charge up to N50 to N80 million to get people killed and we always work as a team. I taught some people to work, some as highway or armed robbers and I usually get my fair share,” he added.

Does Money Ritual Work?

If you ask any random Nigerian this question, they're going to answer with an unshakable conviction that, indeed, money ritual is real and potent. They may not have tried it themselves and they may not approve of its morality, but they'll defend its efficacy with all the strength of their believing heart. Having said this, there are three categories of attitude to the money ritual question:

First are those who strongly believe in its reality and efficacy.

Second are those who think it's more likely to be real than not - they're the sceptical believers.

Third are those who strongly believe it's neither real nor efficacious. This category of people are in the minority and are most likely to be highly educated and intellectually oriented.

But mind you, education and intellect are no guarantees against this belief. In fact, the majority of the well-educated class falls into either of the first two categories. Remember, this is a trenchantly religious society and anything supernatural is neither strange nor bizarre to it. In Nigeria, the metaphysical is as real, if not more so, as the physical.

It's, thus, a fool's errand to try to convince the true believers (who are the overwhelming majority) that money ritual is a scam. It's like trying to convince a Christian that miracles are not real. Good luck with that! However, I'd like to illustrate the battle of belief that currently prevails around the money ritual question. First, are those who are trying to scream from the rooftop that “wake up my people, there's nothing like money ritual”. A good example from this side of the camp is an article written by Ambibola Adelakun who is a brilliant regular columnist for The Punch (the most widely read daily in Nigeria). It was written in 2021 and it presented a sound and very clear-minded arguments against the belief in money ritual. As far as arguments from this camp go, this piece can hardly be bettered. Here is an extended excerpt:

“First, there is nothing like money rituals. By that, I mean there is nowhere in the history of humankind where anybody has made cash appear through magic means. As I stated in a previous article, the belief in the efficacy of ritual killings is typically rife within the context of bewildering economic precarity and the concomitant increase in social inequality. As the gap between the rich and the poor widens in a society, the desperation to overcome the expanding class divide drives people to engage in all sorts of activities they hope will redistribute some of the wealth in their society in their favour. That is why—and this has grown worse in the past few years—many Nigerians have been serially scammed through various Ponzi schemes that promise humongous returns on investment. That is not even counting the kalokalo economy promoted in religious houses where all kinds of seed-sowing are supposed to translate into miracle wealth.

If it were possible to conjure money as our people believe, Africans would be the wealthiest people in the world. We are the poorest and the perennially backward continent partly because we seek supernatural solutions to issues that can be resolved through logic. Look at the recent drama in Ondo State where some people believed that some white clothes fell from heaven. Even when the textile owner insisted that a mere gust of wind blew the materials from where she hung them, people insisted they fell from heaven! That is the nature of our society—people looking for metaphysical explanations to clarify otherwise simple phenomena.

No magic whatsoever makes a business enterprise successful either. Africans who traffic in stories of how supernatural power has prospered certain business people do so largely to rationalise their economic situation while someone else within their community succeeds. They find it hard to accept that someone else, other people can succeed through the ethics of hard work, prudence, and sheer ingenuity, and so they reach for supernatural explanations to self-justify.”

But Abimbola could have as well be spitting into the wind. Her argument is not likely to change even one mind from the believer or semi-believer’s camp. The vast majority of those who hold this belief don't read newspaper articles or read anything at all. And the ones who do read also have their own counterarguments. The sceptics, well, probably remain sceptical and it would probably take something of a demonstrative experiment (shall have more to say on this later) to knock them firmly into the disbelievers’ camp. But even such demonstrative experiment is absolutely powerless in shifting the conviction of a believer by one bit. Such believers will tell you of numerous reported and personal anecdotes of rituals and charms delivering the goods (whatever it happens to be).

And talking about counterarguments from the other side, there was in fact one, and from no less than a former permanent secretary in the Federal government and a professor of public administration. His response, which followed a mere eleven days after Ms. Adelakun’s article, was directly aimed at the latter’s piece, and it was in no less a prestigious national daily, The Guardian, Nigeria. The writer of this counter-piece, Tunji Olaopa, did a very good job in undermining Abimbola's arguments but not by directly engaging with them. Instead, he attacked the meta-logic of her argument: that is, he questioned the logic of applying logical analysis to a phenomenon rooted in metaphysics. Of course, he did not register the fact that he was himself using logic to disqualify Abimbola's logic. He writes:

“While saying “there is nothing like money rituals” assumes logic, and the logic of economic calculation, it is to assume too much about the capacity of logic to explain the whole of life and its many mysterious and dark crevices.”

Further down in the article, he elaborated on the above paragraph:

“Can logic encapsulate the whole of life? That is by itself a logical impossibility. And this is why the line of discourse Adelakun has started is not something she is equipped to carry sufficiently by far, by the logic of her logical explanation. And this is because that logic obviates the possibilities of those realms that different faiths and religions gesture at, the realms that occultic practices take for granted, and the realms that even philosophy dares not disregard.”

Cultural worldviews make people amenable to different beliefs and practices that do not need logic or reason to flourish. In simple terms: what people believe is what people believe. And what people chose to believe cannot be undermined by the disruptive strength of abstract and cold logic, like the one deployed by Abimbola Adelakun. That article, read by millions of people will not stop ritual killings, or the belief in it. What would rather happen is that those who read it would likely shake their heads in consternation: how could anyone say there are no money rituals? And a possible answer from them would likely be: well, only someone who is well-to-do and lives in oyinbo5 land.”

I strongly doubt that Prof. himself believes in the efficacy of money ritual, but he likely believes in its metaphysical possibility. So, here's a member of the highest elite class by any measure (political power, education, intelligence, and socioeconomic status) providing a very powerful argumentation for why the pervasive belief in money ritual cannot, and, in fact, should not be explained away. Hence, those who do believe strongly in it can cite him, and others like him, as authority. And believe me, there are vastly many more like him. I scoured through a lot of research papers by Nigerian academics while working on this piece, some of them published in international journals, and a significant majority of these researchers struck a narrative tone that clearly indicated they lean more to the side of a belief in the reality of money ritual. Most of the studies were designed with the objective, not of challenging the validity of this belief but in tracking its prevalence, causes, and solution. To cite just two examples: first is this 2023 paper by three academics from three different reputable Nigerian universities. Here's their concluding remark on why people shouldn't engage in money rituals:

“One can equally resist the urge to indulge in evil and mischievous acts irrespective of all odds. This study concludes that the Igbo communities should outrightly shun money making rituals which are aberrations to the true essence of rituals and the philosophy of hard work in Igbo land.”

Note that their argument for why money rituals should be shunned doesn't hinge on whether it's valid and efficacious, but only because it's an “aberration”. Another paper, again by a team of authors, also proceeded to take for granted the validity of ritualistic material wealth. In their own argument against, they championed abstinence on the basis that the tradeoffs involved in the very specific ritual they chose to focus on in their study is not worth the effort:

"Again, since the oke-ite charm6 is believed to accelerate an individual’s predestined accomplishments in weeks and years and that of his generation, it is expected that the consequence of that action is a poor generation filled with sickness and untimely deaths. Reasons scholars with indepth insight into this ritual process warn against indulging in it. Most individuals especially the youths have continually disregarded this warning and have indulged in this ritual in their quest to make quick wealth and fortune damning the consequences."

Conclusion

There's no doubt that the claim that money can be made to appear in huge quantities through ritualistic mechanisms is false. However, it is difficult, and perhaps impossible, to settle this question once and for all for the same reason it is difficult to prove that prayer doesn't generate miracles. These things are notoriously confounded by random temporal coincidences. My pastor prayed for me a week ago, and today I got a job. Good luck trying to convince the believer that his God, let alone his pastor’s prayer, in fact, had nothing to do with the job. The exasperating part, however, are the other far more statistically superior instances of prayers, rituals, and other such invocations not working as expected. There are zillions of arguments that could easily be generated for these failures. All that is needed for any such claim to take root forever in the minds of those who believe is one single instance of lucky coincidence. It becomes an eternal reference case gaining wide cultural purchase. It is thus a truism that while evidence may intially be sufficient to trigger and implant a belief, once the belief is established, evidence is no longer sufficient to dislodge it.

You need not bother specifying the country as the phenomenon appears to be almost synonymous with Nigeria. While not unheard of in some other Sub-Saharan countries, it is relatively rarer in those places compared to Nigeria.

A colloquial term used to describe a situation in which an unsuspecting passenger boards a vehicle manned by person(s) with criminal intentions.

A phrase used as a linguistic shorthand for one’s ancestral relatives who live in rural communities and are believed to be behind the misfortunes of anyone who previously escaped their clutches by moving to the city and becoming successful. The assumption is that these conclaves of bitter and resentful village elders are never happy about such success stories, the more so if this runaway Joseph fails to appease these geriatric representatives of ancestral forces back in the village.

A term popular in local politics that refers to the practice of politicians leveraging the hunger of the masses as a way to gain their votes.

The Yoruba word for white people.

It is a type of ritual that involves the severed parts of human beings and animals in an earthen ware pot alongside numerous kinds of herbs and concoctions which is believed to bring wealth to an individual after a certain period of time.” Okeke et al. (2023). It should, however, be noted that this particular description is procedurally not different from every other type of ritualistic processes involving the generation of money. The name is merely an artifact of culture as well as cultural branding.

Unfortunately, that's one of the most basic realities of life in Nigeria. When people read reports of ritual killings, they don't go "Grrrrrrrrrrr!!! Who does that in this 21st century!?" Rather they feel sympathetic for the victim. The practice is ontologically normal and so they just prayed that they and theirs won't ever be a victim. Mind you, if they caught one of these ritualists, chances are high they'll lynch him to death as has happened many times.

You get the scale of the rot when you consider that high ranking politicians, spiritual figureheads and law enforcement officers are sometimes perpetrators and collaborators. People generally condemn the act but never question the underlying beliefs that sprout it.

Although it probably won't help Nigeria much, I do think these kind of articles are important for English speakers to see. Most have little idea about what it's like to live in countries like Nigeria, or how strange African cultures can be.

I can personally attest to the way Americans pound the table, gnash their teeth, and get one another fired over relatively minor issues, while Nigerians are starving to death, unable to read, or, evidently, killing each other in magical rituals. The Western press really doesn't like talking about Africa, so many people never realize how normal violent crime is, despite how readily available statistics are. Even if the phenomena you describe are deeply undercounted, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_intentional_homicide_rate still reports Nigeria has roughly four times the murder rate of the United States; South Africa has about nine times the rate. Oyinbo may be unwilling or unable to actually do anything about it, but our being ignorant about it helps no one.